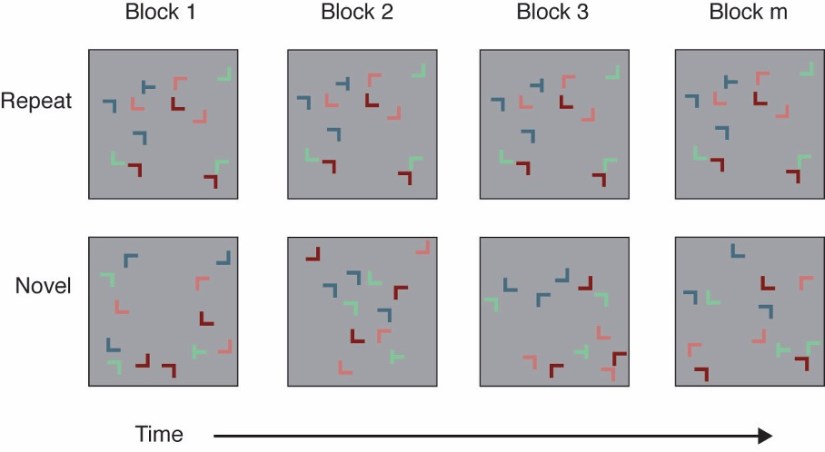

Scientists use computer tasks to engage a brain network and manipulate subtle conditions to infer causation. To understand unconscious memory, we used a simplified visual search task. Here, observers must find a “T” shape among “Ls”, which are rotated and different colour to engage attention. Using these types of grid displays, we can tightly control elements of the task, such as in-putting statistical rules that govern how objects will appear. Observers don’t know these regularities are present, so the question is, will they notice and will it chance their ability to search for the target?

In a 20 minute session, we can quickly see that people not only learn these complicated regularities, but they do so without realizing they’re learning anything. THe ability to find and identify the ‘T’ target getrs much faster and better in displays with mathematical regularities that were repeated over time. This advantage was compared to other displays, in the same task, where the layouts were random, or contained regularities that were not predictive of the target. This phenomenon is called implicit learning.

In a novel application of brain stimulation, I combined this task with activation of the frontal and patietal cortex in ways that altered netwoek excitability. I then observed how this change in neuroplasticity affected implicit learning compared to placebo stimulation that does not affect plasticity.

We altered the learning!

Brain stimulation of these areas actually disrupted the implicit learning process. My paper discusses what this means for our understanding of learning and memory and how to optimize learning about the environment in certain ways.

Read the paper here: Cortex, 2018

Statistical Learning in the Real World

Searching through a crowded visual scene for a target item requires the brain to filter the relevant information from irrelevant information and direct visual attention in a goal-oriented manner. Think of needing to find your friend in a crowded music festival. If you know your friend is wearing a red shirt, you can exclude all non-red objects in order to direct your attention more efficiently.

This type of goal-directed attention is based on explicit knowledge, and involves a part of the brain known as the parietal lobe, along with other connected networks and brain dynamics. We know this based on much research, but in particular, because people with brain damage to part of the parietal cortex known as the intraparietal sulcus have severe problems with spatial attention and visual search.

Yet goal directed attention isn’t the only way we can search our environments. Imagine you don’t know what colour shirt your friend was wearing. Or where to find them. How would you complete the search?

One way to do it would be to slowly scan the area in a systematic way, left to right, top to bottom, and rely on an exhaustive search method. However, this is slow. And research shows we rarely search in an exhaustive way. Instead, we often rely on information stored in the brain as implicit memory. These are based on likelihoods learned from past experience.

For example, perhaps you’ve gone to festivals with your friend before and you have come to learn some information that can help you predict where to find them. Maybe you know what colour shirts they are most likely to wear, blues and reds, rarely yellow or green. Perhaps you have learned what location of the festival they are likely to visit, such as food stalls or the front of the stage. This type of probabilistic information may not be subject to your conscious awareness, but it can help direct your attention. And can do so much more efficiently than an exhaustive search.

How does this type of implicit search differ from explicit search in terms of it’s reliance on the parietal cortex? Can people with damage to the parietal lobe instead direct their attention based on implicit information, despite having difficulties searching based on explicit information? Can we use brain stimulation to modulate activity in the cortex and change the way people search based on implicit memories? These are the questions that guide my PhD research.

In a standard visual search scenario, it will take you a few moments to find the “T” and indicate whether it is facing the right or the left. If the position of the “L” items, known as distractors, is random each time you search, you would slowly get better at the search task, simply via practice. However, if the location of the L distractors follows a statistically reliable pattern, one that is too complicated for you to notice consciously but one that your visual system is highly sensitive to, you will get increasingly better than when the Ls are random. This improved ability to direct attention to a target when the display is statistically reliable is known as implicit learning.

When I used electrical brain stimulation to modulate parts of the visual attention network, namely the left prefrontal cortex and left posterior parietal cortex, individuals were slower to learn these statistical patterns. This findings showed for the first time that activity in the frontoparietal cortex was directly involved in how implicit knowledge about statistical regularity governs behaviour in a visual search task. Read more about these findings in my published work here and here.